The Domain Name System (DNS)

• 14 min read

What I learned about DNS so far.

My understanding of DNS was always pretty basic. But since I started working more with hosting infrastructure, I’ve learned a lot more about it. I think DNS is really cool, but it is complicated. DNS has a lot of moving parts and terminology you need to know about to really get it. So I decided to write a bit about this. Mostly to capture and solidify my learnings, but maybe it can also be useful to others.

In this post I’ll cover what problem DNS solves, what DNS is, and how DNS works when you visit a website in your browser. This post gets a bit technical at times, but I try not to assume any prior knowledge, so you can (hopefully) also follow along if you’re new to the topic.

Why do we need DNS?

The internet is a massive system of interconnected computer networks. And devices connected to this network communicate with each other by sending “packets of data”. But to make sure that these packets are routed to the correct destination, a protocol must be followed.

What’s a protocol? It’s basically a set of rules that need to be followed to achieve “something”.

For example, to mail a letter, the protocol is that you must:

- Use an envelope.

- Write the sender and delivery address on the envelope (using a name, street address, city and zip code).

- Use a postage stamp.

- Deposit the envelope in a mailbox or at a post office.

But if one of these rules is broken (e.g. because phone numbers were used for rule 2 above) the letter will not be delivered.

It’s a bit like that on the internet, but the protocol that’s used is called the Internet Protocol (IP). And instead of using mail addresses to deliver mail to the correct destination, IP addresses must be used to deliver packets of data to the correct destination1.

IP addresses are unique identifiers. For example, if a device wants to visit this website it must (at the time of this writing) go to the IP address 76.76.21.212.

IP addresses work great for machines and robots because they love numbers. But us humans usually have difficulty remembering them, and we prefer using a more memorable domain name instead.

But on the internet IP addresses must be used, so how can you for example type a domain name in a web browser, and somehow still end up at the correct IP address? Well, this is the main problem that DNS solves: DNS can look up the IP address of a domain name.

What is DNS?

Practically speaking, DNS is like a phone book3 for the internet.

Technically speaking, DNS is a distributed naming system that consists of many servers spread across the globe.

I like to think about DNS as a very large partitioned database that organizes, stores, and retrieves information about domain names. To do all of this, DNS has the following main components:

- The domain name space (to organize domain names).

- Name servers and resource records (to store information about domain names).

- Resolvers (to retrieve information about domain names).

The domain name space

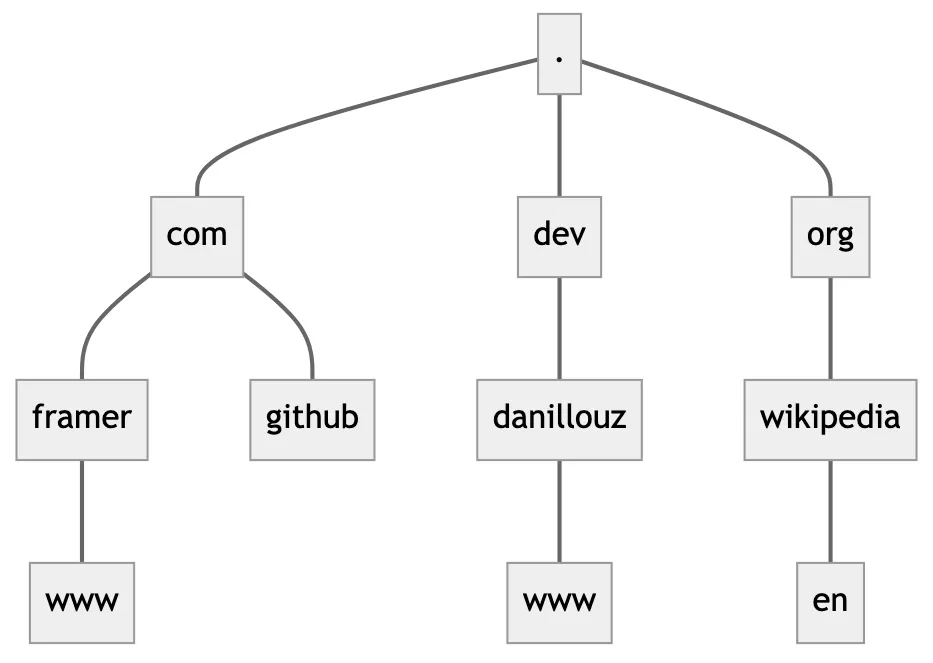

The domain name space is a conceptual model that organizes all domain names on the internet, and it can be visualized as a hierarchical structure that looks like a tree.

This hierarchy is reflected in domain names themselves:

- Each part of a domain name that is separated with a

.(dot) is called a label. - Each label represents a node in the tree, and is a “sublevel” in the naming hierarchy.

- The root of the tree is the “nameless” label

.(dot), also called the root domain4.

For example, the labels of the domain names:

www.framer.comgithub.comwww.danillouz.deven.wikipedia.org

Can be visualized in the domain name space like this:

Top-level domains and subdomains

By following the tree of the domain name space from top-to-bottom, the labels of a domain name go from most generic (.) to most specific (e.g. www). And depending on what “level” these labels sit in the tree, they are referred to differently.

When reading a domain name from left-to-right:

- The right-most label is called the top-level domain (TLD). There are different kind of TLDs5, but the most notable are:

- Generic top-level domains (gTLDs), like

comororg. - Country code top-level domains (ccTLDs), like

ukornl.

- Generic top-level domains (gTLDs), like

- The label before the TLD is called the second-level domain (2LD). And the label before that is called the third-level domain (3LD). This can go on and on: fourth-level, fifth-level, etc. But often all labels before the 2LD are just called a subdomain.

For example, for the domain name www.bbc.co.uk:

ukis the TLD (ccTLD).cois the 2LD.bbcis the 3LD.wwwis the 4LD.

Name servers and resource records

Each label in the domain name space will usually have some information associated with it (e.g. an IP address). This information is stored in text files called resource records (usually called DNS records), and DNS servers that store resource records are called name servers.

There are different kind of resource records, and I won’t cover all of them in this post, but 3 important ones are:

- NS records store the name server of a domain name.

- A records store the IPv4 address of a domain name.

- CNAME records point to another domain name.

DNS zones

Name servers are grouped together into DNS zones and each zone has an operator: an organization responsible for managing a specific part of the domain name space.

DNS zones usually don’t map to domain names or DNS servers exactly, so they can be a bit ambiguous. But they will usually map to level(s) of the domain name space tree (like the root zone, but more on that later). This means that zones (i.e. name servers) only store parts of the information in the domain name space.

I like to think about DNS zones as partitions of the entire database. DNS needs to store a lot of information (and make it globally available), so it splits up its database into zones. And to make sure the system as a whole scales and runs reliably, each zone has an operator that’s responsible for it.

Resolvers

Name servers only store part of the domain name space, so how can DNS retrieve information for every name in the domain name space? Well, most name servers just point to other name servers, and its up to a different kind of DNS server called a resolver (also called a recursor) to follow these “pointers” and retrieve resource records.

How does DNS work?

So far we’ve covered the main components of DNS, but to understand how it works we first need to explicitly identify the different kind of DNS servers and how they interact with each other.

There are 4 different kind of servers needed to make DNS work:

- Root name servers are the name servers that serve the DNS root zone. This is a special DNS zone that contains all TLDs of the domain name space. The DNS root zone consists of 13 root name servers6, and each root name server contains the root zone database. This is a list that maps all TLDs to the IP address of their name servers (called the TLD name servers). Such lists are published as plain text files called DNS zone files (like the root zone file).

- TLD name servers store zone files that map all 2LDs (for a specific TLD) to the IP address of their name servers (usually the authoritative name servers).

- Authoritative name servers have complete information for a domain name, and are the “authority” for that part of the domain name space.

- Resolvers receive requests from a client (e.g. a web browser) to find resource records (e.g. an IP address). Resolvers send queries to name servers, and receive resource record(s) back as an answer. Depending on the query type (i.e. what resource record is being queried), a resolver might need to query multiple name servers, but (for uncached queries) it will always start with one of the root name servers. That’s why every resolver stores a hard-coded list of all 13 root name servers. And by default the resolver of your Internet Service Provider (ISP) is used when you browse the internet7.

I used to be really confused about what authoritative name servers are, and how they differ from other name servers. But an authoritative name server is just the name server that “knows” the information being queried by a resolver. So it actually depends on the query type which name server is authoritative. For example, root name servers are authoritative for the root zone, TLD name servers are authoritative for a TLD zone, and when querying the A record for a domain name, the name server that stores the IPv4 address is authoritative.

With that covered, we can finally answer the question below.

What happens when you visit a website in your browser?

The following occurs when a browser uses DNS to look up the IP address of a domain name:

- The browser sends a request to a resolver to find the A record of the entered domain name.

- The resolver sends a query to one of the 13 root name servers to find the TLD name server of the domain name. And when found, the root name server sends an NS record back—with the name of the TLD name server—as the answer to the resolver.

- The resolver sends a query to the TLD name server to find the authoritative name server of the 2LD of the domain name. And when found, the TLD name server sends an NS record back—with the name of the authoritative name server—as the answer to the resolver.

- The resolver sends a query to the authoritative name server to find the A record of the domain name. And when found, the authoritative name server sends an A record back—with the IP address of the domain name—as the answer to the resolver.

- The resolver responds with the IP address of the domain name to the browser.

- The browser can now make an HTTP request to the IP address and fetch the website.

Note that the steps above happen for uncached queries. Since there can be a lot steps needed to look up information for a domain name, resolvers will cache the results of queries. So when a query is made for a domain name that was recently looked up, the resolver can skip (some of) the steps above and return the cached result immediately. Caching can happen at every step above, on the name servers, resolver, on the browser and operating system.

Bonus: how is the domain name system managed?

We now know that DNS is basically a very large database that’s split up into zones, and that zones are managed by operators. But how do operators work together? How do operators know about changes that occur in the domain name space (like when a new domain name is registered)? And who oversees all of this?

ICANN and IANA

ICANN (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers) and IANA (Internet Assigned Numbers Authority) are 2 organizations that help provide stability and consistency on the internet.

ICANN helps with administration, oversight and maintenance. But delegates some of this to IANA (which is part of ICANN).

For example, ICANN helps make technical decisions on the internet, coordinates adding new TLDs, and operates 1 of the 13 DNS root name servers. While IANA maintains what protocols are used on the internet, coordinates IP addresses globally, and manages the DNS root zone.

Domain name registries and registrars

Besides the root zone database managed by IANA, there are also organizations that manage a database of all 2LDs with a specific TLD. These organizations are called registry operators8. Strictly speaking, the databases they maintain are called registries, but often the operator itself will also be referred to as the registry.

This means each TLD has a registry. For example, Verisign is the registry for .com domain names, and Google Registry is the registry for .dev domain names. Verisign and Google actually manage multiple TLDs, but there are also registries that manage a single TLD.

So how do these registries know about (new) domain names? Well, some registries allow you to directly register a domain name with them. But most registries will partner with a different organization called a domain name registrar.

Domain name registrars are companies that allow you to register domain names by paying them a fee. When you register a domain name, you don’t actually buy the domain name. But you will hold the “right” to use it for a specific amount of time. You then become the registrant of the domain name and will be considered the “owner” of it.

Registries allow registrars to partner with them by entering a Registry-Registrar Agreement. But in order to do so, the registrar must meet the requirements9 set by the registry (and ICANN). After the agreement is in place, the registrar may offer their customers to register domain names for the specific TLD(s). And every time a domain name is registered, renewed, transferred, or expires, the registrar will notify10 the registry—where for some operations registrars also pay registries (and ICANN) a fee11.

In closing

That’s it for now! Everything covered in this post is pretty theoretical, and one way to see DNS in action is to query resource records with dig. But I’ll save that for another post.

By the way, these are some resources I used to learn more about DNS:

- RFC 1034: Domain names concepts and facilities

- RFC 8499: DNS Terminology

- What is DNS?

- What does ICANN do?

(and let me know if you have any good ones to add!)

Footnotes

-

The IP protocol is basically the addressing system of the internet, but there’s more needed to deliver packets from source to destination. The exact details are out of scope for this post, but there’s also a transport protocol needed to define rules how data is sent and received. Ultimately there are multiple protocols needed which are “layered” on top of each other, like TCP/IP. ↩

-

This is an IPv4 address, and IP version 4 has been around since 1983. It works great, but we’re running out of unique IPv4 addresses because nowadays even toasters must connect to the internet. This is where IPv6 comes in: IPv6 uses more characters to make sure all toasters all covered! For example,

2606:4700::6810:84e5is an IPv6 address. But IPv6 is not completely adopted yet, so it’s still common to use IPv4. ↩ -

In case you don’t know, a phone book is literally a book of phone numbers And a long time ago, they were used to find a phone number for a person or business when you only knew their name. (Yes, people would actually call each other!) ↩

-

The root domain is typically not specified. For example, you’d usually type

github.comin your browser instead ofgithub.com.(note the trailing dot). But you can absolutely do this! And when you do explicitly provide the root, the domain name is referred to as a Fully Qualified Domain Name (FQDN). ↩ -

There are 6 types of TLDs: country code (ccTLD), generic (gTLD), generic restricted (grTLD), infrastructure (ARPA), sponsored (sTLD), and test (tTLD) top-level domains. ↩

-

There are 13 clusters of hundreds of physical DNS root servers, distributed all over the globe. And you can see them (and their location) on root-servers.org. ↩

-

But you can change this in the network settings of your operating system and use a different resolver, like Cloudflare’s 1.1.1.1 or Google’s 8.8.8.8. ↩

-

Registry operators (or registries) are sometimes also called a Network Information Center (NIC). ↩

-

These requirements can differ per registry (and some make them available online). For example, most registries require the registrar to be accredited by ICANN. And sometimes registries even set rules that affect which registrants may register a domain name for their TLD (e.g. only US governments may register a

.govdomain name). ↩ -

Registrars usually use the Extensible Provisioning Protocol (EPP) to interact with registries. ↩

-

The registrar must pay fees every time a domain name is registered, renewed or transferred. There’s the registry fee (as defined in the Registry-Registrant Agreement). And the $0.18 ICANN fee. But there might also be other fees, like a yearly fee of $4000 when the registry is ICANN accredited. ↩

Webmentions

Loading...

Thanks for reading!

If you have ideas how to improve this post, let me know on GitHub.